The Museum will be closed January 12th - January 16th in preparation for our new Special Exhibition Ripley's Believe It or Not!. Museum reopens Saturday January 17th. New Exhibit opens January 31st!

The final scene of the classic movie, “Indiana Jones” shows the crated-up, priceless Ark of the Covenant being wheeled away into the depths of a massive warehouse filled with boxes of every conceivable size. As it joins the other artifacts, it became another faceless, nameless rectangle, vanishing into the vast piles of boxes.

The mysterious box.

Room 10 at our Museum is nothing like that. Our small cadre of researchers and curators diligently categorize and sort vast piles of boxes, in an orderly and professional fashion. The knowledge of the curatorial team of our collection gives us proper appreciation for all those seemingly blank boxes . . . and we have a favorite.

On the bottom shelf of the third stack, halfway down the shelving unit, in the cramped and crowded collections room, there is a battered old box, often with other artifacts stacked on top to save room.

The "Aer Nostrum" and its case.

Years ago, we pulled out the wooden crate, which is about 45” long by 15” high and wide, as it was blocking our progress on another project. A member of the Curatorial staff took an interest in it since no one on our seven-member curatorial staff had seen it opened. It took tools and some effort to gain entry; the minimal labeling and notes scribbled in antiquity were mostly damaged, or faded, or missing. “Aer Nostrum” was one of the few legible petroglyphs, along with the enigmatic creator’s name, “G. Betancourt.” Our database was silent about its provenance; it just looked like something interesting was hiding inside. To our astonishment, the box held a treasure.

Label on the model's box.

1929 was an incredibly exciting year, for everyone. The country’s admiration for Charles Lindbergh was at a fever pitch, along with a flurry of other worldwide, mind-blowing news events. Airmen and mountain climbers were conquering the last empty spaces on earth, life was in full bloom – the world-wide recession was only months away but no one knew it. It was a glorious time to be alive. Fantastic airships filled the skies in newsreels, majestic ocean liners drew even distant shores in close, and everywhere, there was innovation and creativity.

The Great War was a fading memory -- industries were bustling with a million new technologies and peaceful advancements. Inventors and industrialists vied to bring the “next big thing” to the hungry crowds, eager to see what came next.

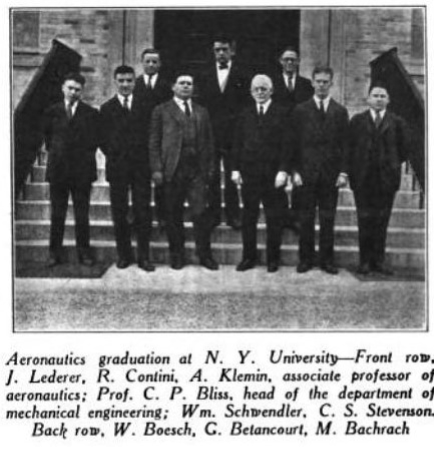

Betancourt, back middle.

In Detroit, Gilbert Betancourt was enjoying it all, playing with ideas that might bring him the level of fame earned by Edison, Zeppelin, and Lindbergh. All over the world, similar minds were coming up with gadgets, vehicles and all sorts of interesting inventions. A writer as well as a tinkerer, Betancourt published many articles on lighter-than-air travel. In 1928, his design for an “Airship terminal” was granted a U.S. Patent. He was focused on the Graf Zeppelin, famous at the time for its long-distance flights across continents. Gilbert spoke in front of Congress on aviation and the role of the airship. In his workshop, he pulled out the plans he’d drawn three years earlier of a fantasy, a dream so large it could no longer stay on paper. Betancourt knew he had to build his dream.

This text on Betancout's model gives a clue to some of his aspirations.

From April 1, 1929 until mid-August, the designer spent many hours fashioning his airship design into a 42-inch highly detailed model. His creation combined all the latest features of airships, from the unique multi-finned control system of the U.S. Navy’s brand new “ZMC-2” blimp to the landing bumpers fitted to the enormous “Graf Zeppelin.” Betancourt’s “Aer Nostrum” was not just bigger, it was of a size unmatched by any other rigid airship. Years in the future, the 800-foot-long “Hindenburg” was designed to carry less than 100 passengers in relative comfort. The “Aer Nostrum” was drawn to carry 1,000 passengers; it was intended to be 1,000 foot-long and nearly 300-feet in circumference. He saw it as a replacement for ocean liners.

Betancourt's notes and signature on the model.

We carefully opened the box and found inside an impressive model, with some fantastic features. Betancourt wired it with lights, and drilled out hundreds of tiny port-holes, to give the impression of how it would look in flight. It has a purpose-built set of supports that attach the oversize model to the top of its transport crate for display. Nearly a hundred years later, it all slips together easily. The expertly painted model is well-finished with a lot of little additions inscribed or attached to its hull. The fin array is intricate and delicate, showing incredible attention to detail. Gilbert included a small scale model of the “ZMC-2” to provide a reference to the airship’s great size.

These early images show the detail of the "Aer Nostrum" model.

The "Aer Nostrum" was only ever a dream, and the dramatic onset of The Great Depression within weeks of the model's completion, sealed its fate. The inventor continued to advocate for large airships but could not find backing - in the end, the crate went into storage, and the still-born airship locked inside only made it out into the light a handful of times in the past century.

Details of the model in Betancourt's workshop.

Today, properly curated and gently returned to its shelf, the "Aer Nostrum" rests awaiting its turn on the gallery main floor, among the Museum's other great airship models, alongside the legendary "Hindenburg", "USS Los Angeles", and the mighty "Graf Zeppelin." It will sit at the dividing line between the "World War I" and the "Golden Age of Flight" galleries, a powerful reminder of what might have been.

It is flying! Or so it was hoped....

2001 Pan American Plaza, San Diego, CA

Phone: 619.234.8291

Información En Español

Contact Us

We would like to thank all our sponsors who help us make a difference. Click here to view all who help us.

The San Diego Air & Space Museum is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. Federal Tax ID Number 95-2253027.